04 Sep Brisa Aviles – Personifying Creative Civic Engagement

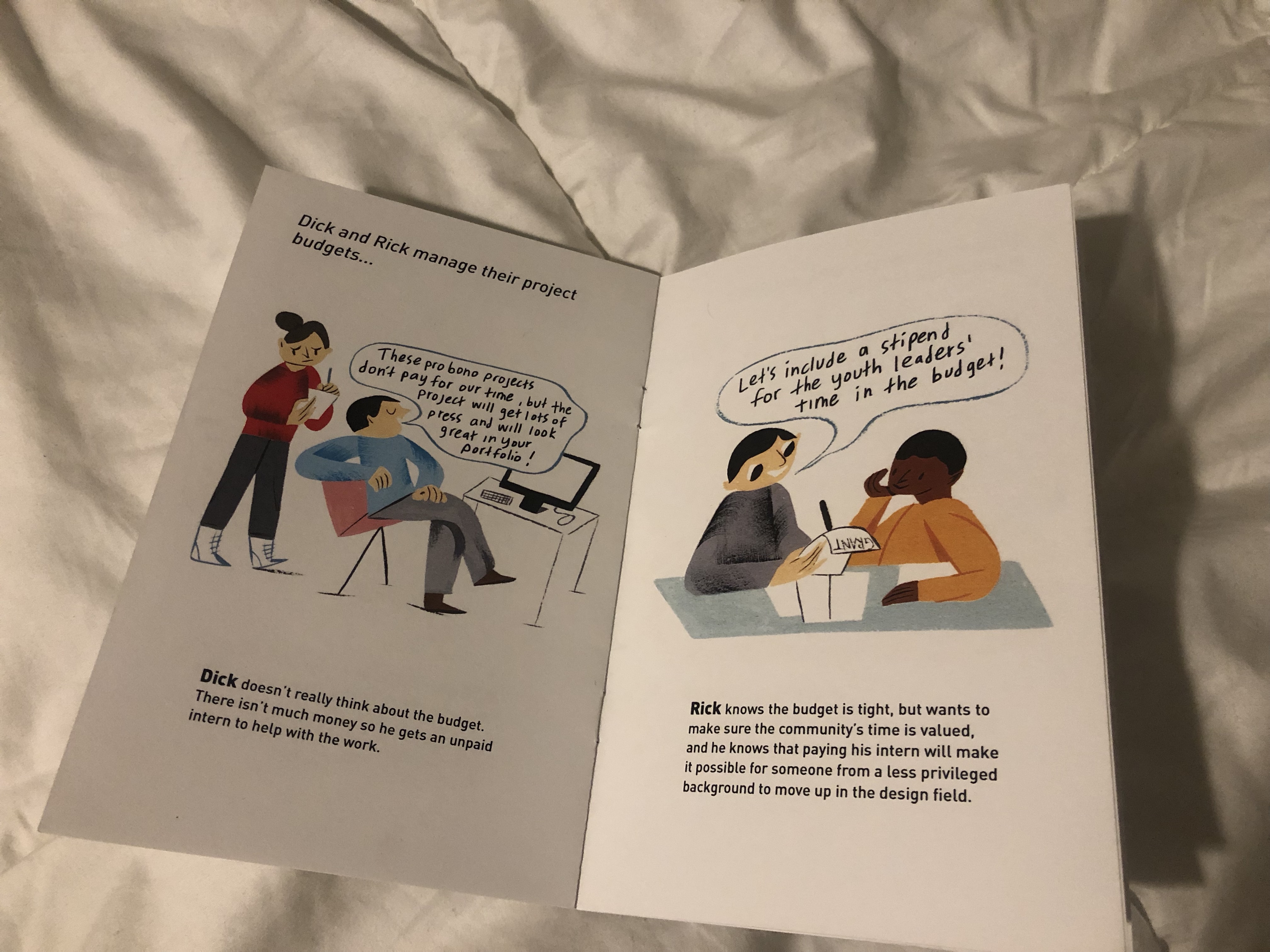

As we conclude this month’s module, I realize that the topic “creative civic engagement” has come to mean many things to me. First and most importantly, it emphasizes the importance of incorporating community voice into public projects. Although this framework may seem simple, it requires a multitude of steps to ensure the community participation from residents is genuine and impactful. We used “Dick and Rick: A Visual Primer for Social Impact Design” put together by the Equity Collective at the Center for Urban Pedagogy, to explore why this framework is critical for creative civic engagement work. Both Dick and Rick are designers and both have their methods of involving community. While designing a park for the community, Dick incorporates residents’ feedback once, to ask residents what color they think the swings should be. While it is true that he involved the community in his project, it was done at a surface level and didn’t allow for the community to discuss what their greater concerns for the park were. On the other hand, the designer Rick prioritizes making time to listen to residents problems and creates a space for them to shape the proposal. Rick’s approach resulted in designing a park that activated the space because residents felt a connection to it. This visual primer helped me understand just how critical it is to allow communities to be at the forefront of public projects. Without their involvement, projects can’t reach their full potential. To continue the module, we began to look at real life projects that used a Rick approach. Many of them were put together by artists groups and collectives and focused on giving power back to communities, especially in areas that have been stripped from the opportunity to engage with art and owning their agency.

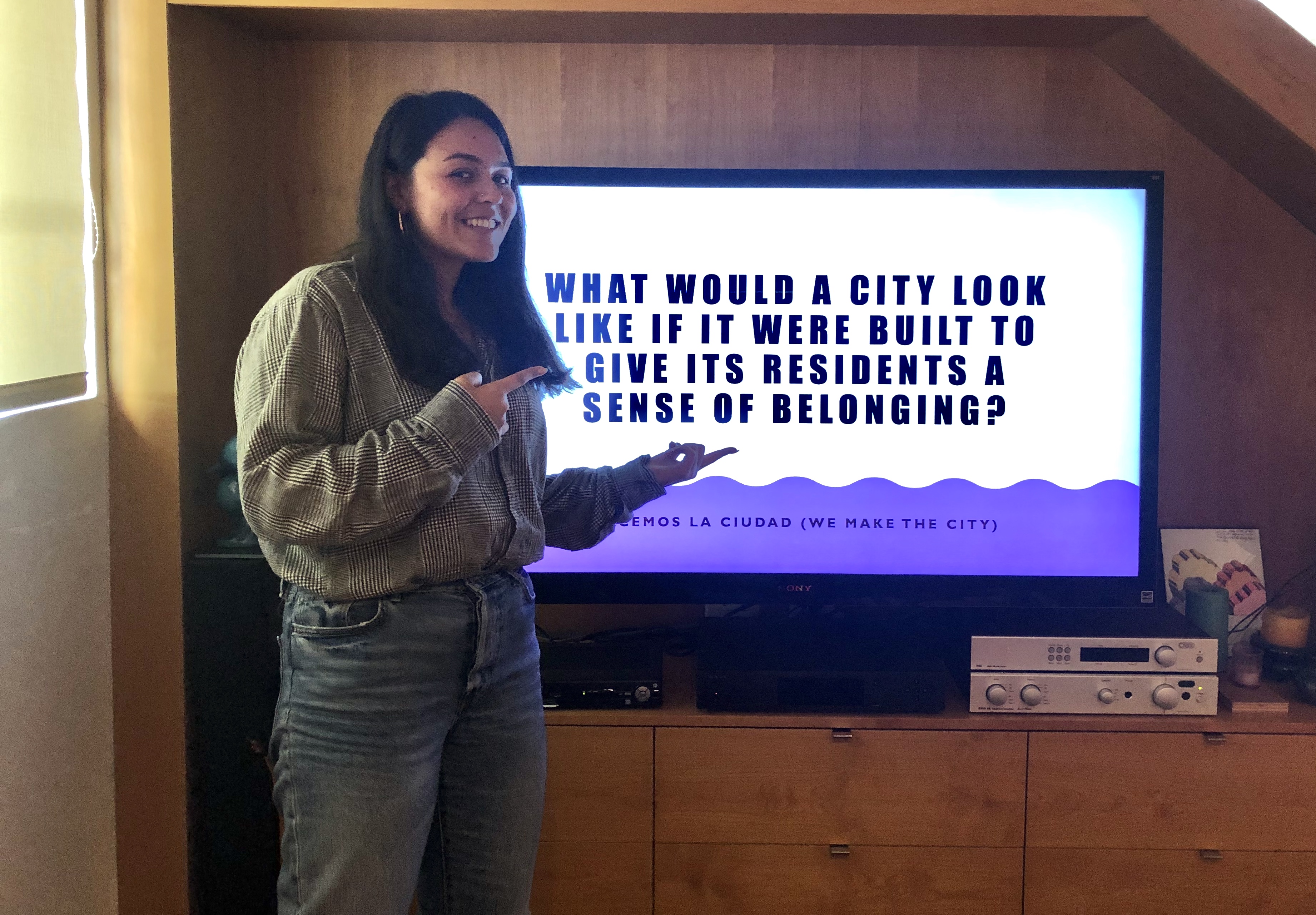

Together and individually, the Fellows explored artists, designers, art collectives, and groups, some being Rick Lowe: Project Row Houses, Maria Gaspar: 96 acres, Las Imaginistas: Hacemos La Ciudad, and more. An observation I made about these groups was that many of their projects exist in under-served communities of color, which often times have limited to no access to the arts. These groups practicing creative civic engagement recognize that the limitations to art strips away communities powers’ to speak. Using their collective knowledge and skills, the artists set up a framework that allowed residents to be the guides when drafting solutions that address issues in their communities. Many can think of this work as just “art” but it also plays a critical role in creating civic action. They motivate community members to get involved and see their neighborhoods through a different perspective. These art projects go beyond the artists point of view because they incorporate other people’s creativity. Although the artists are often times outsiders of the communities they work in, their personalities make it easier for them to be accepted by residents. The fellows explored how the personality of an individual is just as critical as the creative civic engagement approach itself.

All of the artists we observed carried a sense of humility, patience, and openness. The humility it takes to do this work is in my opinion the most critical because you recognize that you aren’t doing this with expectations of something in return. This work is done because it recognizes the privilege of having the formal knowledge to bring together skills and guide a vision. These projects aren’t about monetary returns, they are about recognizing that assets can exist in communities that have been conditioned to think of themselves as poor. Patience is also a critical trait because coming in as an outsider of a community, trust isn’t easily established. Trust from residents can take time, but it is crucial to remain patient because you need the residents for the work to truly resonate with the community. Trust can be established by showing up to events hosted by communities, be willing to learn about culture and language, and interact with residents in ways that aren’t related to the project. Lastly, artists also possess the trait of openness. As a creative, a vision is what starts the idea of a project. Although there is an existing vision, it does not mean the vision is going to stay that way for the entirety of the project. Artists must be willing to change what they had initially planned due to resident feedback. Without these traits working with a creative civic engagement framework will be difficult because it won’t allow you to think beyond what you have already been told about that community.

Ultimately, the concept that truly sticks with me from this module is seeing the extraordinary in the ordinary. A person navigating their community everyday is conditioned to think of things as just belonging in the spaces they are. Sometimes we may not think why those things exist there. The concept of exploring the extraordinary in the ordinary really made me start thinking about my everyday spaces and what makes them special. I have started to admire things such as informal public spaces where people know to gather to feel a sense of community. For instance, the Jack in the Box in my hometown San Ysidro where the typical fast food chain has become a regular stop along the border city for commuters. People gather at all times of the day to wait for their rides, drink their coffee, use as shelter on cold or hot days, eat breakfast, or get a few minutes of rest before work. Without belonging from the neighborhood, you would think it is a typical Jack in the Box, but to me, it is a staple to understanding what a border commute is like. It is extraordinary to me how everyone in that community knows how the Jack in the Box is used. I start to think just as deeply about these things as I navigate Los Angeles. I pay attention to what is being used in a community and what isn’t, the missing histories being told, and what things stand out. I attribute this concept to teaching me how to think critically of those overseen gems in Los Angeles.